PMG Collection Inspiration: Indigenous Americans

Posted on 11/25/2025

The United States celebrates Thanksgiving this week — a holiday where families come together to give thanks for the important things in their lives and celebrate prosperity, usually with a feast. The first American Thanksgiving was a celebration held by the Plymouth Pilgrims and the Wampanoag Native American tribe. To celebrate the roots that indigenous Americans have in our modern Thanksgiving holiday celebrations, here are 10 notes steeped in indigenous history.

Ten Notes Celebrating Indigenous Americans

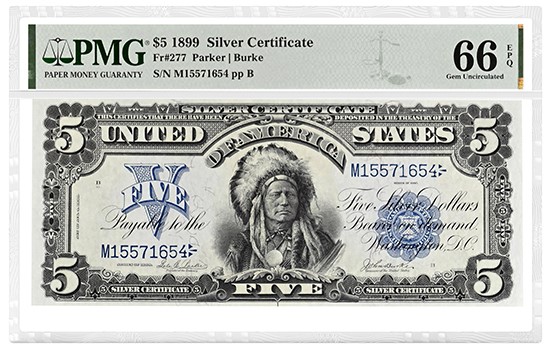

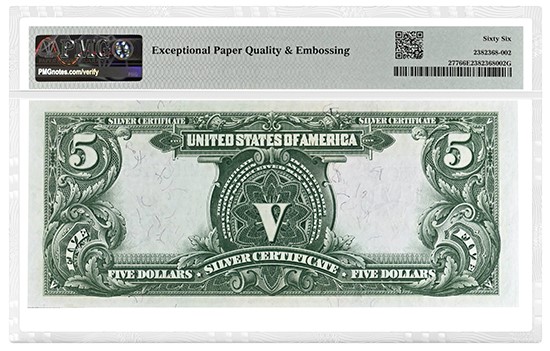

Running Antelope (c.1821-1896)

The United States 1899 $5 Silver Certificate note — often called the Indian Chief Note — is the only US federal paper money currency to feature a named Native American. Despite this significance, the 1899 series note has drawn controversy because of the incorrect depiction of Running Antelope (Tȟatȟóka Íŋyaŋke) wearing a Pawnee war bonnet. Originally, Running Antelope’s portrait was engraved wearing his three-feathered headdress, but the headdress did not fit in the allotted space on the note, prompting G.F.C. Smillie — the note’s engraver — to swap the headdress for the Pawnee bonnet.

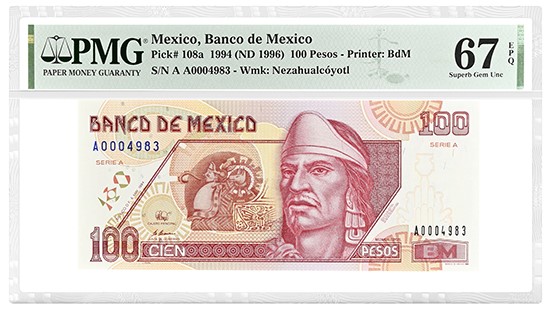

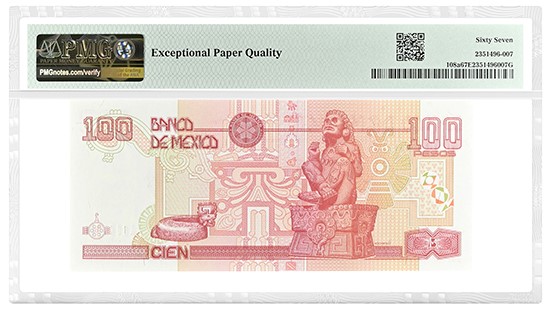

Nezahualcoyotl (1402-1472)

Depicted on the Mexico 1994 (ND 1996) 100 Pesos, Nezahualcoyotl was a high-profile warrior responsible for the fall of Azcapotzalco in central Mexico and the rise of the Aztec Triple Alliance. Regarded as a sage and poet-king, he brought about the Golden Age of Texcoco, bringing artistry, scholarship and the rule of law to the land. In addition to being a ruler, Nezahualcoyotl was well-known for his poetry. His poems continued to be passed down after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire before finally being written down in the 17th century.

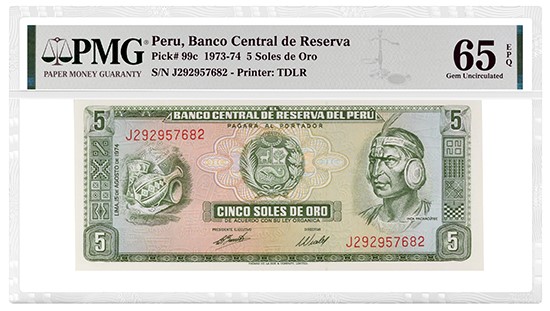

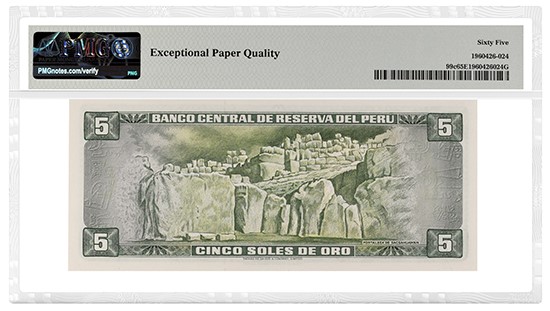

Pachacuti (early 1400s to mid-1400s)

The front of this Peru 1973-75 5 Soles de Oro depicts Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui — also called Pachacútec — the ninth Sapa Inca of the Kingdom of Cusco. During his reign, Pachacuti conquered much of southern Peru and the northwestern territory that would become Quito, Ecuador, to establish the Inca Empire. Additionally, Pachacuti is credited with creating and expanding the cult of Inti, including the creation of the traditional Inti Raymi celebration of the winter solstice. Modern scholars and anthropologists consider Pachacuti as one of the first historical emperors of the Incas and the cosmological representation of the beginning of the Inca Empire.

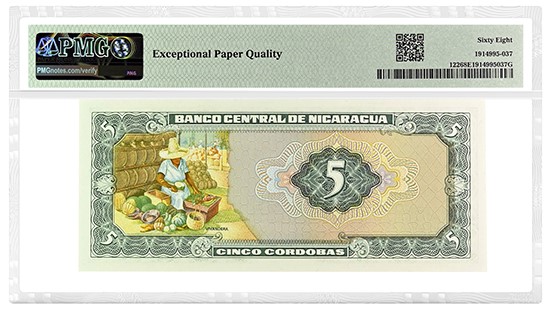

Nicarao (1485-1540)

Nicarao — or Macuilmiquiztli — was consider the most powerful cacique (or tribal chief) in pre-Columbian Nicaragua. When Spanish conquistadors arrived in Nicānāhuac (western Nicaragua) in the early 1500s, Macuilmiquiztli initially welcomed them with open arms. However, the Spanish army, led by Gil González Dávila, lost the trust of Macuilmiquiztli and the Chortegas when they began stealing gold and baptizing the Nahua people without permission. Macuilmiquiztli and the Chorotegas waged war against the invaders and successfully forced them to retreat to Panama, but they were eventually defeated at the hands of several Spanish conquistador fleets in the Spanish conquest of Nicaragua in 1524. Macuilmiquiztli remains a national hero to the Nicaraguan people and is depicted on this Nicaragua 1972 5 Cordobas.

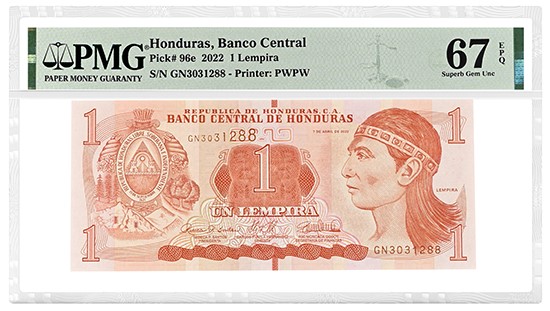

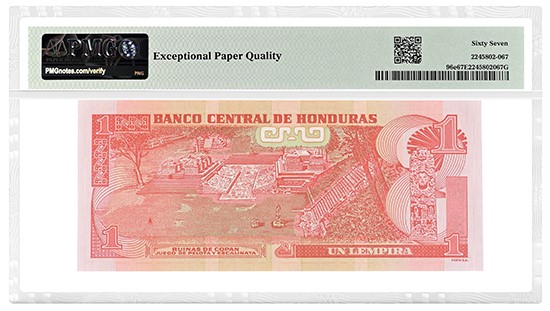

Lempira (1499-1537)

In Honduras, “El Indio Lempira” is a holiday celebrated annually on July 20 in celebration of Lempira, a Lenca chieftan who led a resistance against Francisco de Montejo and his attempts to conquer southwestern Central America. Apparently, he was so powerful that the conquistadors feared him because they could not kill him. The Lenca people still survive to this day, with many living in Honduras and El Salvador. Lempira is featured on this Honduras 2022 1 Lempira, which is named after him.

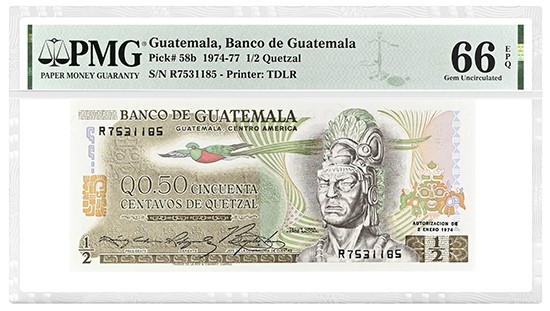

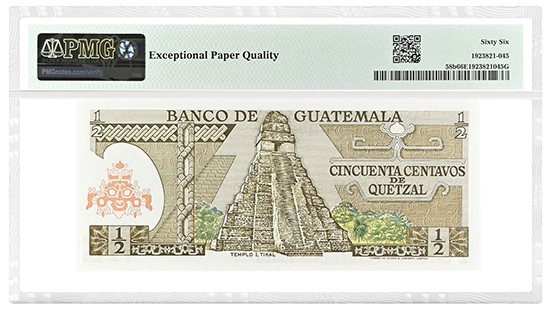

Tecun Uman (1499-1524)

Tecun Uman is portrayed on the front of this Guatemala 1974-77 Half Quetzal. Unfortunately, his official history is not well documented, so much of the current understanding of his life is rooted in legend. Tecun Uman was one of the last rulers of the K’iche’ Maya people who fell during the battle of El Pinar in the Spanish conquest of Guatemala.

Uman is now Guatemala’s national hero and has inspired many tales about his legendary last stand against the conquistadors. One of the most prominent legends tells of his companion — a quetzal bird — that accompanied him in battle. When Uman fell, the quetzal, overcome with grief, lay its body on Uman’s bleeding chest, staining its feathers red. From that day on, all male quetzals bear a scarlet breast and are never heard singing.

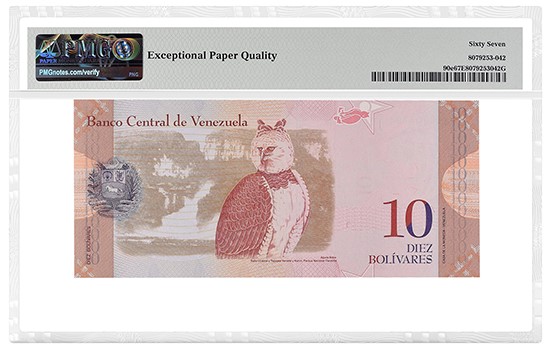

Guaicaipuro (c. 1530-1568)

Guaicaipuro is one of the most celebrated Venezuelan caciques. Though the area occupied by the Teques was populated by several indigenous groups, Guaicaipuro’s tribe was the largest and most feared. He united all the surrounding tribes under his command after successfully planning several ambushes against the Spanish conquistadors, becoming their resistance leader and chief. Today, Guaicaipuro is still recognized as a source of inspiration to the Venezuelan people, both in forms of resistance groups and as a centralized figure to bring awareness to the role of Venezuela’s indigenous peoples. He is portrayed on this Venezeual 2014 10 Bolivares.

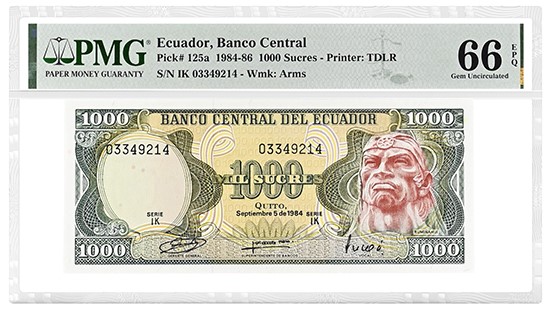

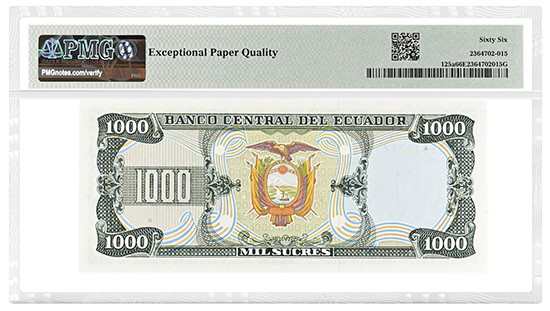

Rumiñawi (c. 1490-1535)

The front of this Ecuador 1984-86 1,000 Sucres shows Rumiñawi, a formidable general during the Inca Civil War. He was the right-hand man of Inca Emperor Atahualpa, who ruled over the Inca Empire until his capture and execution by Spanish conquistadors in 1593. Enraged by the conquistadors — who executed Atahualpa despite Rumiñawidelivering a ransom for his release — Rumiñawi purportedly ordered the Treasure of the Llanganates thrown into a lake and met Sebastian de Benalcazar for a final confrontation, where he was defeated. As the Spaniards closed in, Rumiñawi ordered the burning of the ancient city of Quito and the death of the ñustas, the temple virgins.

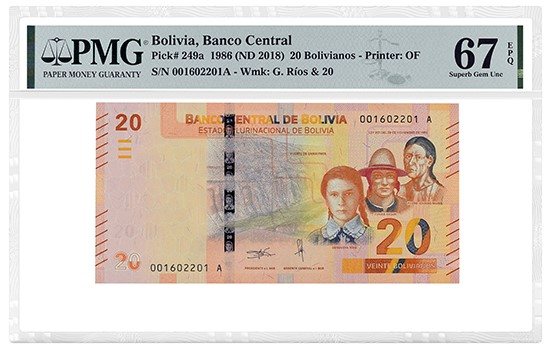

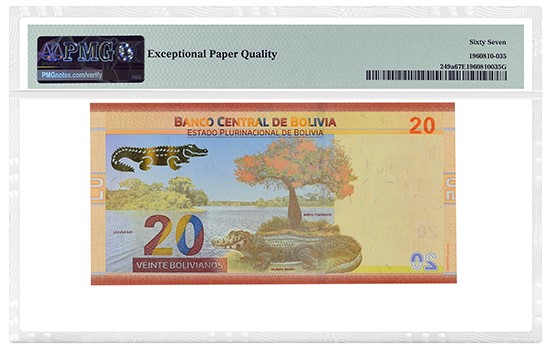

Genoveva Rios (1865-?), Tomas Katari (?-1781) and Pedro Ignacio Muiba (1784-c.1811)

Three Bolivians are featured on the front of this Bolivia 1986 (ND 2018) 20 Bolivianos: Genoveva Rios, Tomas Katari and Pedro Ignacio Muiba. Rios is recognized for protecting the Bolivian flag during an invasion by Chile during the War of the Pacific. Katari, an indigenous Aymara, was the leader of a peasant uprising who revolted against the appointment of outsider caciques to their townships. Finally, Pedro Ignacio Muiba was a famous indigenous leader whose rebellion in 1810 would become a catalyst for future Latin American independence movements, which eventually led to Bolivia securing its independence in 1825.

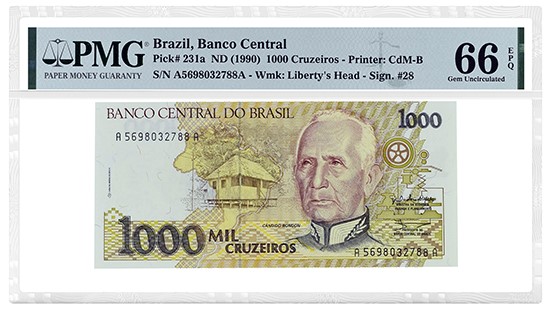

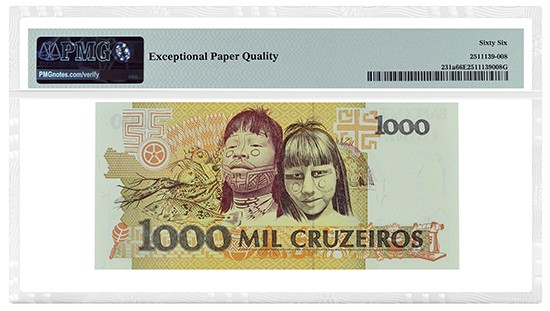

The Karajá people

The back of this Brazil ND (1990) 1,000 Cruzeiros note depicts two Karajá. The Karajá are an indigenous people who have lived in central Brazil since at least the 1600s (European explorers first contacted Karajá tribes in 1673). Currently, they reside in at least 29 villages dotted across the Araguaia River valley. In recent years, many of the Karajá have integrated themselves into Brazilian society while simultaneously preserving their own culture.

If these notes inspired you, check out our other Collection Inspiration columns for more collecting ideas, including 11th century notables, ancient goddesses and women warriors. Also, be sure to follow PMG on Facebook, Instagram and X for articles and interesting notes posted daily.